Indigenous yeasts, exogenous yeasts

It’s the cat tamer Chris. Today I’m going to tell you why I like indigenous yeasts… to the point where I shout about them to my friends! True story… for when we get together for a beer (because being shouted at might be one of your fantasies?).

First of all, what is yeast used for in wine?

Yeast is a single-cell fungus, a micro-organism, which enables alcoholic fermentation by transforming the grape’s sugar into alcohol. This is why the more sunshine a vintage gets, the sweeter the grape becomes (thank you photosynthesis), and higher the alcohol percentage in the wine is. Makes sense! and it’s perfectly natural.

Secondly, let’s learn the terms:

- Indigenous yeasts aka “natural yeasts” aka “wild yeasts” generally come from the grape. They can also come from the equipment and the environment in the wine cellar. We talk about yeast in the plural because you can find between 5 and 20 different strains during spontaneous fermentation. They vary throughout fermentation and from one year to another.

- Exogenous yeasts, called “chemical”, “oenological” or “added” yeasts, are all natural too (yeast cannot be created artificially, it’s grown) but they’re chosen. There is a huge amount (+250) and they are marketed based on the properties the buyer desires: revealing aromatic compounds, extracting polyphenols, controlling the fermentation temperature, flavouring (yuck), etc.

In these exogenous yeasts, there are two main categories:

-

- Neutral, it kick starts fermentation and dominates its environment

- Aromatic, which we find a lot in mass-produced wines, like “grapefruit flavoured” rosés (God, help us)

You saw at the top that without yeast, there’s no fermentation, so no wine 😱.

The best is spontaneous fermentation, fermentation which starts on its own thanks to indigenous yeasts. But it’s not as simple as it seems! Because there’s life everywhere and wine yeasts are in competition with mould, other yeasts like brettanomyces (you know the ones, that stable smell), oxidative yeasts… I could go on, an entire bacteria ecosystem which can alter the wine. Making a “natural” wine is like painting a Rembrandt (see for yourself).

Are you following? So even if the indigenous yeasts have a certain authenticity, as the yeast is an integral part of the terroir ("terroir is 50% soil, climate, exposure and 50% indigenous yeasts" says Jules Chauvet), we always prioritise taste, the quality of the wine. So when there’s a risk of a deviation here – for example when it’s been a particularly rainy year which leads to some of grapes on the vine rotting – even if I'm not for it, I understand the use of neutral exogenous yeasts. They help to trigger fermentation avoiding any deviation. And so we prioritise the taste, the intrinsic quality of the wine, all while protecting an expression of the terroir.

To sum up, I really like the idea of indigenous yeasts, because they line up with my quest. And yet, it’s impossible for 99.99% of people to distinguish between indigenous yeasts and neutral exogenous yeasts in the taste of a bottle; compared to aromatic yeasts, which can be identified as they often flavour the wine in an unsubtle way.

So, the next time you go to see your wine merchant, trust them and don’t try to put them on the ropes with sulphur and indigenous yeasts. It’s more complicated than it seems… and if they’re good (we know loads, have a look), they’ll only recommend good bottles! Oh, and then be honest with yourself, would you slap Mike Tyson?

Thanks for your attention. Now, if you want to share your opinion, join us on Instagram.

Wine & Cheese pairing

The marriage of wine and cheese is a centuries-old tradition, an ode to fine dining! In France, the land of 400 cheeses, there are many pairings options, here are a few:

Hard cheeses

Hard cheese and dry white wines: Comté, Beaufort, Salers, Emmental and Gruyère are the perfect companions for dry white wine, whether they tend to be oxidative or not, like the wines of Jura and Southern Burgundy. Ossau-iraty, Manchego, Parmesan and Pecorino come alive with more robust dry white wines like Côtes de Gascogne (dry), the Chenin Blanc of Cahors, the whites of Languedoc.

Step off the beaten track with Sunny Caaaaaaat.

Goat’s cheeses

Goat’s cheese with a Loire white wine: Anjou Noir, Sancerre, Pouilly Fumé, Quincy, Reuilly, Menetou-Salon… the fruity notes of these wines will glorify the light and fresh notes of goat’s cheeses. Pairings with light rosés will enhance the wine!

Adventurous? Try a pairing with Cosmic Caaaaaaat!

Soft cheeses

Soft cheese and red wine: Brie and Camembert are delicious with a light and delicate red wine from Burgundy, Beaujolais, Alsace or Loire. The soft texture of these cheeses will envelop the light tannins, their flavours will reveal the fruit, sometimes even the floral notes of the wines.

Blue cheeses

Blue cheese and a red wine or a sweet white wine: for lovers of reds with cheese, opt for a Roquefort or a Gorgonzola paired with red wines from Corsica, Languedoc-Roussillon and the Rhône Valley. The black fruit and spicy aromas of these wines will envelop the intense and spicy aromas of the blue cheeses.

Why not a Karate Caaaaaaat?

For Gex and Termignon blue cheeses, or Picón Bejes-Tresviso, a sweet wine (ideally botrytised) will reveal a surprising pairing for the taste buds: the creaminess from the residual sugar in the wines will harmonise with the delicacy of these cheeses, exalting the complex bouquets of the wine: honey, spices, dried and confit fruits, toasted brioche, nuts, orange blossom, citrus…

Conclusion

There is no hard-and-fast rule, there are a thousand possible pairings; the personal tastes and preferences being the main factor in your choices. So, if you’re unsure, don’t think about it too much: cheese and wine from the same region! It’s usually a winning team.

What is sulphur a.k.a. sulphites a.k.a. SO2 a.k.a. E220 a.k.a. sulphur dioxide… oh, enough already!

Sulphur dioxide is a colourless gas, with a penetrating smell in its natural form, and discreet when dissolved in a liquid. All fermented products contain sulphur dioxide, coming from the natural process of fermentation. In other words, sulphites are a preservative naturally present in fermented products.

Are you following?

For wine, we use the term sulphites. Even in unsulphured wines, you can have up to 20 milligrams per litre (20gr/L), because sulphites are naturally produced by yeast during the winemaking process. This is why wine with “zero sulphites” doesn’t exist and why we use the term “no added sulphites”.

In the winemaking process, sulphur has been used since the 18th century. The Dutch introduced it in France with the invention of the sulphur fuse (which is used to disinfect the barrels before they are reused). Sulphur has antiseptic and antifungal properties, which inhibits yeast and harmful bacteria, and stabilises the wine. This sulphur is just like anything else: fine in the right amount, bad in excess (like the sun, water, oxygen, chocolate… OK, not chocolate.). It is all about balance.

The WHO has established the maximum daily intake of sulphur as 45 milligrams for someone weighing 65KG (10st 2lbs) ; with the rule of three you’ll see what’s right for you.

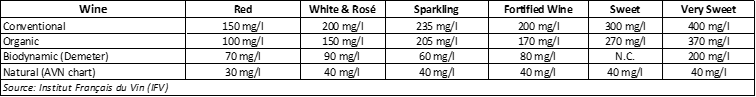

Here’s an informational table on the doses of sulphur authorised depending on the type of winemaking operation:

*AVN: Association des Vins Naturels (natural wines association)

Sulphur is a vast subject; industrial companies in the agrobusiness even add it to fruit (!) and chips (!), in addition to lots of additives and correctives. We are opposed to that. We are artisans, crafters, artists of winemaking, our philosophy can be summed up in one word: respect.

Making natural wine

Natural wines are not only about suphites, it is about how the vineyards are conducted (with plant maceration and “bouillie bordelaise” or with herbicide, pesticide and unatural fertilizers), how the grapes are handled (manually with care, or industrially with machines), how the juice is fermented (naturally or with the help of chemicals)… More is explained on our blog.

Caaaaaaat wines are naturally crafted by Christophe Kaczmarek in collaboration with his friends winegrowers which vineyards are cultivated according to the organic and biodynamic rules. The winemaking is then natural: no added products or chemicals, most of the time not even sulphites, and no filtration, fining or elements which could spoil the wines authenticity.

In all cases, taste is our number one priority.

What is natural wine?

Simply put

By definition, wine is a cultural product. You can’t stumble across some wine out in the wild, it requires the intervention of a winegrower to make it from grapes (those guys are natural).

So simply put, natural wine is a wine which is made as naturally as possible:

- No synthetic products: not in the vineyards, not in the cellar, anywhere

- Manual harvesting

- A total sulphur/SO2 level lower than 40mg/L

In other words, we aim for pure fermented grape juice. Yes, this should always be the case, but it’s not that simple. Nature is capricious and we don’t follow its rhythm anymore.

A bit of History

The history of naturally produced wine goes back to Antiquity, well before the arrival of 20th century industrial winemaking techniques, which were doubly amplified by the Second World War: the rapid development of petrochemicals (notably for armaments) and the race for yield (during reconstruction).

In France in the 1980s, the movement for a return to natural wine production was spearheaded by such illustrious figures as the Beaujolais "négociant-éléveur" Monsieur Jules Chauvet, who was also a writer, scientist and fine wine taster. Jules Chauvet was a pioneer, one of those rare human beings for whom the adjective "genius" means something. As early as the 1950s, he was producing natural wines. His methods slowly caught on with curious minds such as Jacques Néauport, itinerant wine producer, and the emblematic Beaujolais winemaker Marcel Lapierre (and many others).

During the 90s, the natural wine movement continued to gain popularity in France, Italy and Slovenia, then spread rapidly across Europe and the world (including the USA and Australia) from the 2000s onwards.

Nowadays

Today - as the general public becomes increasingly aware of the benefits that such production brings to their health and that of our environment - many winemakers are converting their vineyards or opting from the outset for healthy agriculture and natural winemaking methods.

The image below summarises the differences in winemaking methods:

And as we are seeing a wave of greenwashing, keep one thing in mind: free wine doesn’t exist. Either we pay with cash, or we pay the price by damaging the environment.